Emoji

Open your phone’s keyboard and go to the emojis.

Scroll past the same five emojis you’ve used for years and see what others exist. You will soon see 🍡 🈸 🍙 and other weird-looking pictures.

What the hell are these things, and why are they in your phone?

Short answer? Japanese high school girls.

Long answer? Read on.

Pictorial Communication

Till the early 2007s, most of the internet communicated with good old emoticons. :) or :P or :( or even an adventurous ;-) for the more emotive.

With the advent of Gmail and the iPhone, the world graduated from the basic barbarism that is using :) to represent a smile, into the world of emojis.

Most people took emoji to mean “emo” for emotion and “ji” for … well, who cares?

Yeah, that’s not how you split the word.

Emoji is literally the Japanese word 絵文字 (eh-moh-jee). 絵 means picture and 文字 means letter.

But how did these picture letters get into the iPhone and Gmail?

To answer that question, we need to wind the clock all the way back to 1992. To a Japan when pagers (or beepers) were the rage.

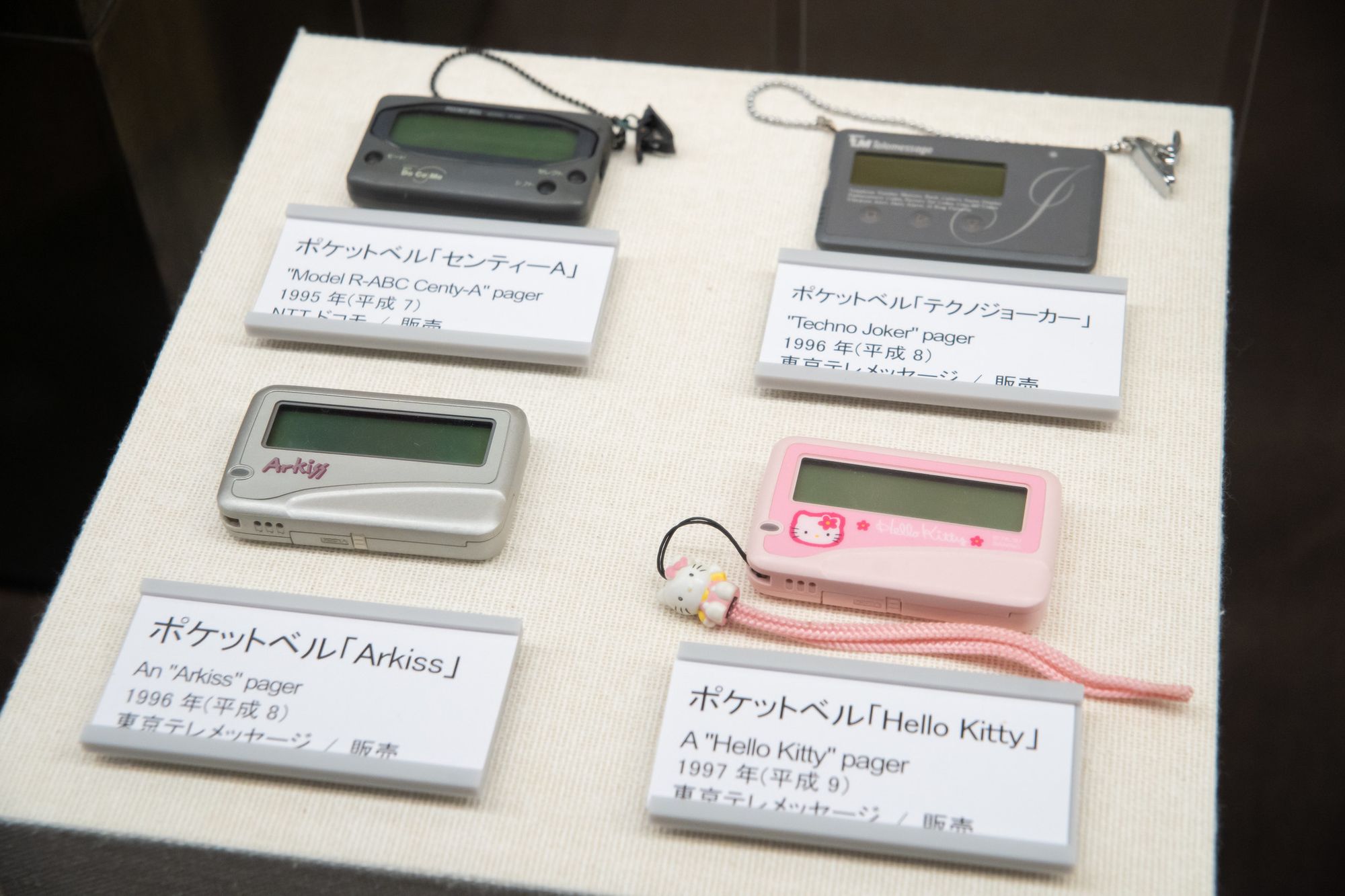

Pagers

Pager (or beepers) were massively popular among businessmen, salarymen (Japanese has no subtlety here – this just means man who works for a salary), and school students. In a population of 120 million, there were 100 million pagers!

NTT Docomo, a private company formed from the former state monopoly company NTT (Nippon Telegraph and Telephone Corporation), had a major share in the pager market.

Here is how these pagers worked in Japan:

Each pager had a number and could do only one thing – receive messages. The sender called the pager's number, dialed some digits to form the message, and hung up.

Now, Japanese has thousands of characters across three types of scripts and there was no natural way of entering them all on a landline phone. So companies assigned numbers to each “alphabet” in the simplest character set (katakana) and distributed the numbers in the form of cheat sheets. Crucially, each company used different numbers for the alphabet.

こんなの出てきた笑

— ボスコニアン (@SxHxNxJx69) March 14, 2020

大阪出てきた頃に渡されたポケベルのメッセージ打ち込み表(?)

関テレて笑

ぼくは比較的携帯電話持ったの早かったんですけど、

ポケベルがまだ全盛の頃ですね、

あと少数は携帯か、ピッチ☎ pic.twitter.com/tQmKwLWpjf

Someone found their pocket bell cheat sheet!

So to send an 愛してる (“I love you”, read as “eye-she-teh-roo”), you would first “spell” it out in katakana as アイシテル (a I shi te ru). Next, you look up each character in your cheat sheet to arrive at the numbers 11 12 32 93. You then call up the pager's number, punch in these numbers, and hang up.

The receiver would receive “アイシテル”, read it out loud, figure out it meant 愛してる and then feel all warm and fuzzy.

Whew. Just typing that made me not want to say I love you. But that’s how these pagers worked. And they were wildly popular.

The heart mark debacle

Someone at NTT Docomo didn’t like this whole spelling-things-out thing and wanted to find a way to send messages with real kanji characters. And they pulled it off.

In 1996 they released their new pager service “FLEX-TD” and presumably patted themselves on the back for improving communication for a whole country.

To their horror, in a few weeks they saw a mass exodus of users to their competitors who were still on the older technology. It was a bloodbath.

It took them a while to realize what was driving this defection: a single character.

See, in their quest to make the entry of kanji characters smoother, some product manager decided to get rid of extraneous symbols. One of these symbols was 💗.

Their core user base was high school girls, who used 💗 at the end of seemingly every message. And it makes sense when you consider that messages had to fit in 10 characters, leaving little room to convey emotion.

After all, there is a world of difference between “Call me” and “Call me 💗”.

As soon as the high school girls realized their favorite character was gone they ditched Docomo and moved en masse to a service that still allowed them to 💗.

i-mode and the Birth of e-moji

The year was 1997. Shigetaka Kurita, a software engineer, had been working at NTT Docomo for 3 years.

He worked in the part of the company that was attempting something revolutionary: an internet-enabled mobile phone service called “i-mode”.

Yes, Japan had mobile phones on which you could browse the internet, all the way back in 1997. Hell, by 2003 you could watch live TV on your phone.

During the hectic development of this groundbreaking product, Shigetaka realized they had forgotten about the heart mark debacle.

After thinking long and hard he took a proposal to his managers.

The e-moji Proposal

The heart mark debacle had shown just how important emotions were in online communication. Shigetaka went a step further and pointed out that emails in Japan (even between friends) tended to be rigid and similar to formal letters.

He wanted to give users the ability to express emotions in their emails. He wanted to go beyond the 💗 and create a whole set of pictograms he called “e-moji” that i-mode users could call upon.

His managers liked the idea and wanted this to be an opportunity for Shigetaka to grow. They agreed to it, on three conditions: Shigetaka would have to build it on his own, he would have to deliver his other work as expected, and the e-mojis needed to be ready in one month to make it in time for the release.

Shigetaka had next to no design experience but took it upon himself, pulling all-nighters to bring his idea to life.

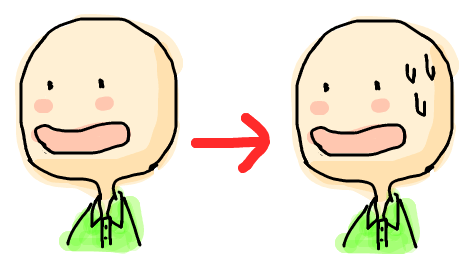

Looking for inspiration he turned to Japan’s rich manga (comics) culture. He realized manga creators had already solved large parts of the “how do you express emotions with pictures” problem.

For example, a bead of sweat on the face represented hard work, a lightbulb represented an epiphany, a closed fist pointed at you was … well, self-explanatory.

He also added some common foods, drinks, daily objects, and a bunch of moon phases (why..?). He took inspiration from signage that everyone recognized and created e-mojis for things like the hospital, post office, gas station, and so on.

In all, Shigetaka’s first set included 176 e-mojis. And just to be really safe, he created not one, but six heart e-mojis. And he made it in time for the release.

Beyond i-mode

NTT Docomo’s i-mode was a hit in Japan and became a defining experience for a whole generation of mobile phone users.

Soon, Docomo’s competitors came up with their own versions of internet-enabled phones.

Now there was a problem. People loved using these emojis to make their messages fun but they were only supported on NTT’s phones.

Other companies came up with their own versions of emojis that only worked on their own phones. This meant messages sent across carriers ended up being garbled, or worse, showed different pictograms than the sender intended.

The right way of fixing this problem would be to create an interoperable standard every company could adhere to.

The Japanese companies made their case to the Unicode Consortium, a non-profit standards body that creates the Unicode standard. The Unicode standard is a list of all characters across all known languages and how they should be represented on computers. This is the standard that enables us to use computers in languages other than English.

The Unicode Consortium was not particularly enthusiastic about the emoji proposal. The scope of their work was actual languages and emojis were not a language.

Going Global

When the iPhone was launched in Japan in 2007, Masayoshi Son, the founder of Softbank Group, was adamant that the iPhone would never succeed in Japan without emoji support. Masayoshi remembered the heart mark debacle of a decade ago.

Thanks to his persistence, Apple introduced a version of the iOS keyboard where users could enter emojis. Once iPhone users outside Japan realized they had this rich set of pictures to use, emojis caught on like wildfire.

In 2010, emojis that began life with Shigetaka's effort and evolved over a decade, were finally added to the Unicode standard thanks to Apple and Google.

Emojis have since then seen many revisions and some of these have marked milestones in our keyboards. For example, in version 15.1 we got the ability to add skin tone to emojis. Other revisions addressed gender stereotypes – previous versions only had male police officers, female nurses, male-female couples, and so on.

Emojis have now evolved to the point they can star in films like the 2017 “The Emoji Movie” (never seen it, but IMDB rating: 3.7/10)

And there is your story arc: starting with Japanese high school girls who ditched pagers for their 💗s, all the way to those weird emojis on your phone.

Polysemy

During the research for this piece we found this fascinating example of how deeply communication is tied to culture.

In academic literature, emojis are called “polysemous”. Polysemy is the capacity for a symbol to have multiple related meanings.

Since emojis were originally created for a Japanese audience, some make no sense to people outside of Japan, or have been given different meanings than they were originally created for.

In our research we found these. See if you can spot any familiar ones:

🙆♀️

What it means in Japan: “Ok!!” (like making an O with your arms)

What it seems to mean outside Japan: One of the steps for the “Y M C A” song.

🙅♀️

What it means in Japan: “Nope.”

What it seems to mean outside Japan: I know karate

🙏

What it means in Japan: “Please!!” (when making a request)

What it seems to mean outside Japan: Namaste

Also: High five!

🍘

What it means in Japan: Senbei (Japanese rice cracker)

What it seems to mean outside Japan: Skyscraper silhouette in a beautiful sunset

💨

What it means in Japan: Took off really fast/running

What it seems to mean outside Japan: Gas of unknown provenance

💁

What it means in Japan: “Here it is” (こちらでございます)

What it seems to mean outside Japan: Sassy woman

🙇

What it means in Japan: Dogeza

What it seems to mean outside Japan: Push ups

Did 🫵🏻 👍🏻 this article❓

If yes, 🙏🏻 ✍🏻 ⬇️

With 💗,

1️⃣ from 🇯🇵 Team