A peek into Japan’s Hot Springs (Part 2)

Editor’s note: This is the second of a three-part post. Part 1 can be found here.

The Hot Spring Act of 1948

Lest you think any old well could be an onsen, the Japanese government has very clear rules on what can be called an onsen.

These are set forth in the Hot Spring Act of 1948. This law defines 1) what criteria qualify a groundwater source as an onsen and 2) the safety standards for operating an onsen.

The Rules

Every onsen must satisfy at least one of two conditions:

- The water temperature at the surface should be above 25 °C (or)

2. A kilogram of water should contain at least one of the 19 substances in concentrations above the threshold:

- Dissolved substances (excluding gaseous substances) >1000mg

- Free carbonic acid (CO2 ) >250mg

- Lithium ion (Li+) >1mg

- Strontium ion (Sr++) >10mg

- Barium ion (Ba++) >5mg

- Ferro or Ferrion (Fe++, Fe+++) >10mg

- Manganese ion (Mn++) >10mg

- Hydrogen ion (H+) >1mg

- Bromine ion (Br-) >5mg

- Iodide ion (I-) >1mg

- Fluoride ion (F-) >2mg

- Arsenate ion (HAsO4-- ) >1.3mg

- Meta arsenite (HAsO2) >1mg

- Total Sulfur (S) [corresponding to HS-, S2O3-- , H2S ] >1mg

- Metaboric acid (HBO2) >5mg

- Metasilicic acid (H2SiO3) >50mg

- Sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3) >340mg

- Radon (Rn) >20×10-10 Ci

- Radium salt (as Ra) >1×10-8 mg

Safety

If you think about it, the geological processes that create hot springs are not very far from the ones that create magma in volcanoes.

Toxic gases are a major concern at onsens and not accounting for these gases has led to fatalities.

One common substance in onsen waters is hydrogen sulfide. Readers might remember this from high school chemistry as the gas that smells like rotten eggs.

While this is true, it only holds true in low concentrations. At higher concentrations, hydrogen sulfide is a lethal gas that first kills the sense of smell. It is a colorless gas, so humans have no other means of detecting it. Hydrogen sulfide can incapacitate and kill an adult in just a few minutes.

This is why the Hot Spring Act defines what safety standards operators need to obey to safely run an onsen.

The Hot Spring Analysis certificate

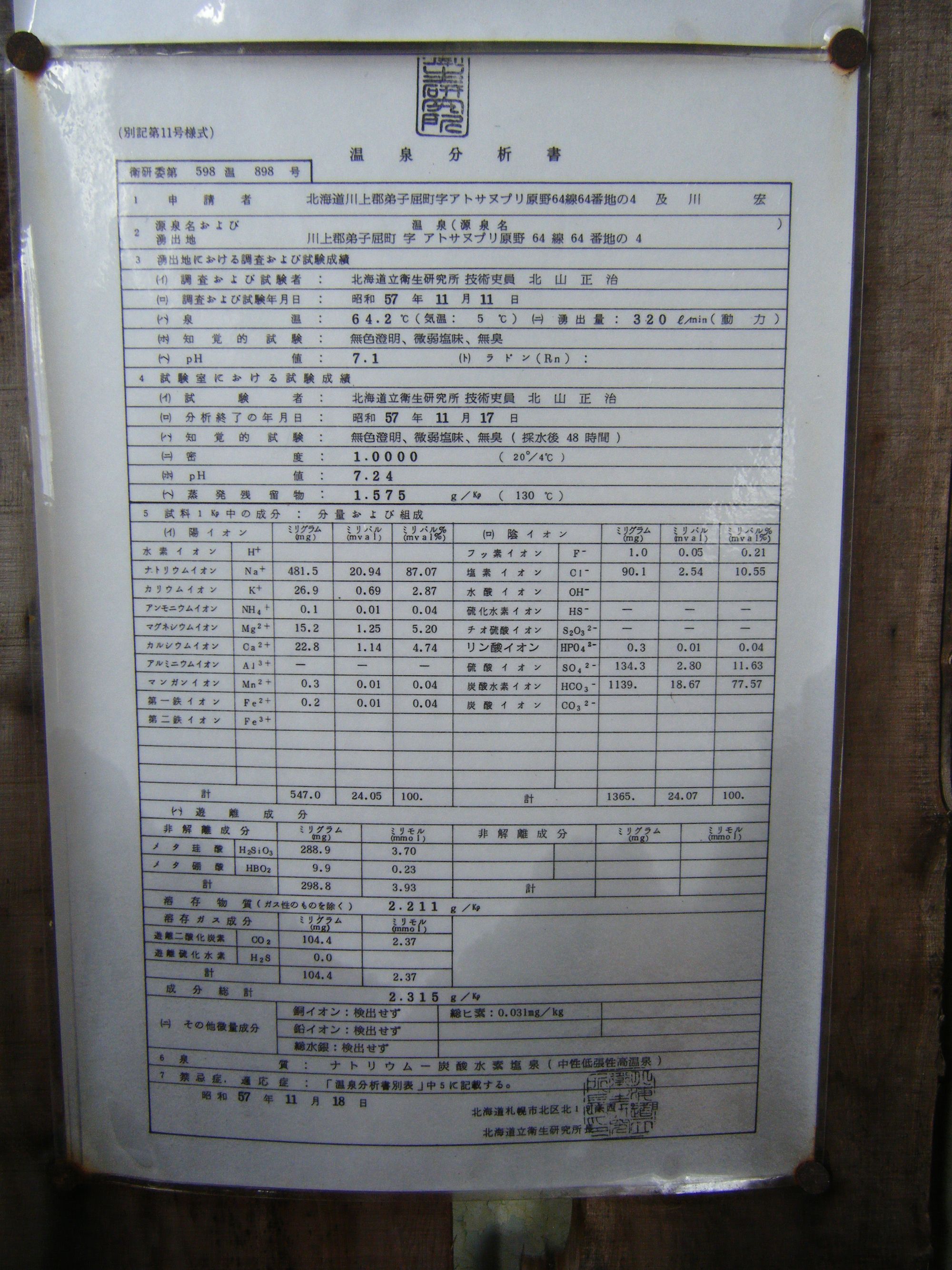

The next time you visit an onsen keep an eye out for the Hot Spring Analysis certificate (温泉分析書). The Hot Spring Act mandates this must be prominently displayed at the entrance of every onsen.

This certificate is a test result from a laboratory that notes the temperature and substances dissolved in the onsen's waters. It is an important legal document which proves that a hot spring meets the criteria to be called an onsen.

But why do people care about this piece of paper, you ask?

Because a) it certifies the spring can legally be called an onsen, and interestingly b) it tells visitors what benefits they can expect from the onsen.

Indications and Contraindications

You see, healing is an important theme when visiting an onsen.

Onsen are classified according to the dissolved substances in the waters. Each classification is then given a set of “indications” and “contraindications”.

For example, acidic onsens have an indication of “good for chronic skin conditions like atopy” and a contraindication of “stay away if your skin is sensitive to UV light”.

Onsen-goers often visit specific onsen with the goal of benefiting from such indications.

In fact, avid onsen-goers consult a whole slew of resources on indications and contraindications. Most of these resources are in Japanese, but this article provides an overview of onsen classifications and their benefits.

Scientifically speaking

There is a vast body of knowledge spanning thousands of years that soaking in an onsen is beneficial to health. But is there any scientific evidence that onsens actually help cure the problems they claim to cure?

I am no expert in this field, but the few peer-reviewed papers I read seem to have mixed results.

Japanese journal papers (like this one) conclude that trials between onsen-goers and control groups showed statistically valid evidence that onsens help with certain ailments.

Other papers like this review from 2009 suggest the research isn’t strong enough to draw a firm conclusion.

There is also a theory that such benefits might be confounded by the fact that subjects are taking themselves out of their regular routine, traveling to the onsen, spending time in leisure (away from their stressful lives), often in the middle of beautiful, natural settings. Perhaps the benefits are the outcome of all these factors, rather than the chemicals dissolved in the water alone?

The scientific jury is probably still out on this one, but centuries of experience should count for something and I can leave it at that. It might not cure my knee pain but I certainly look forward to every onsen trip.

If anyone has peer-reviewed research with a different viewpoint, please reply to this post and I will read the paper and update the post.

But how does this all even work?

Why is there hot water in the ground? And why does it have these dissolved substances?

The oversimplified answer is “Because rain water seeps down and the inside of the earth is very hot.”.

Readers might remember from high school physics that the earth is made of many layers and the core of the earth is molten metal at >6000 °C. All that heat needs to go somewhere, doesn’t it? The heat from the core transfers to the layers above it, successively heating each layer.

For every kilometer you drill below the surface, the ground temperature rises by 25 °C. In volcanic areas like Japan though, the temperature rises by almost 40 °C every kilometer.

Rain water that seeps from the surface heats up as it travels down the earth and collects in cavities underground. This is the water that is pumped up as an onsen.

In areas close to volcanoes, magma is an additional source of underground heat. Magma is often at 900 – 1000 °C and can be found just a couple kilometers beneath the earth’s surface.

In addition to heating the water table, chemicals in and around the magma also interact with the water, infusing it with some of the 19 chemicals.

Onsen close to volcanoes often have temperatures well above what one might call pleasant.

Oniyama Jigoku, an onsen in Beppu, for example, has a surface water temperature of 99 °C. Perhaps that is why the name aptly translates to “Demon Mountain Hell Spring”.

Well, how about all these dissolved substances, you ask?

Arima Onsen is a great example to look at. The hot spring is ~350 meters above sea level, many kilometers away from the sea. But minerals dissolved in the waters closely resemble seawater.

How? Fossil water.

Millions of years ago, seawater got trapped deep underneath the earth’s crust due to the movement of plates. The water has no way of escaping, and is thus preserved or “fossilized”, making it fossil water.

This seawater, already rich in minerals, absorbs ions from the rocks surrounding it over the millions of years it is trapped underground.

Hot Springs and Energy

Japan’s location at the collision zone of multiple tectonic plates means it is sitting on a metric fuckton of geothermal energy. ~10% of Japan’s electricity needs are stored in the form of heated water right below its surface. Yet, it is 10th in terms of installed geothermal power, producing just 600 megawatts (the total installed capacity of all plants in Japan is 243 gigawatts).

In a fascinating clash of technology, culture, and communication, geothermal power is vehemently opposed by onsen owners who fear their businesses will perish if all the hot water underground got sucked up by the geothermal plants.

This is where some science communication could go a long way. Geothermal plants run on water or steam well above 100 °C and under high pressure. To get this steam, geothermal plants must drill to depths of about 2,000 meters, far deeper than the aquifers that feed onsens.

After the steam has been used to rotate the turbines, it is condensed into water and pumped back into the bowels or the earth so the plant never runs out of umm… steam.

Onsens as a Business

Despite all the hype in Part 1 about onsen being an integral part of Japanese culture, as a business, onsens are now a struggling sector. There are a multitude of reasons that we will touch upon. Honestly, this is the part I enjoyed writing the most... <Continued in Part 3>