The shoe that became a sock. And then a shoe again.

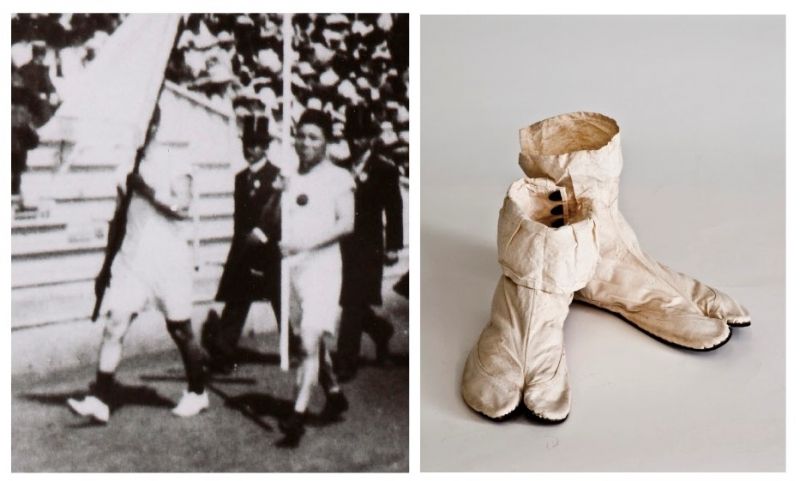

Stockholm, 1912

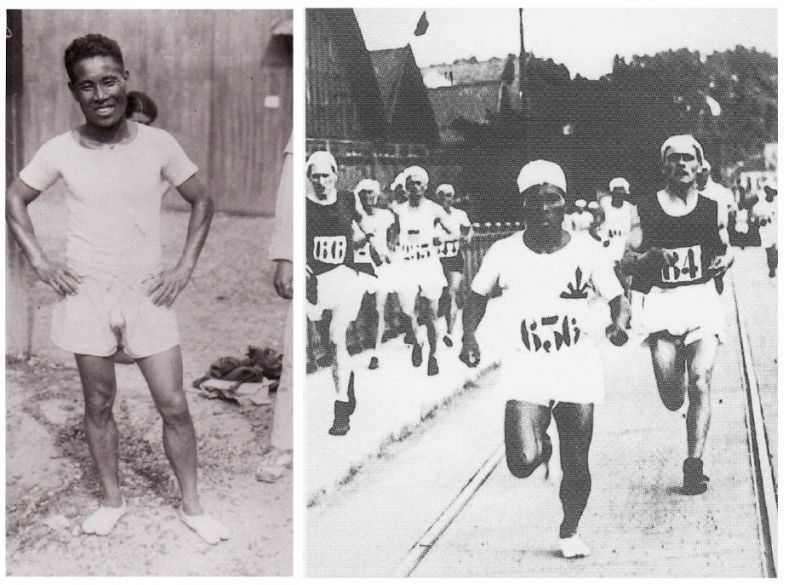

At 35° C it was an unusually hot day for Stockholm. Shizo Kanakuri stood at the start line of the marathon in the 1912 Stockholm Olympics. Shizo was carrying the hopes, dreams, and pride of Japan, a country attempting to become a “modern” nation.

There was something that made him stand out from the rest of the runners though.

He was the only one not wearing shoes.

Shizo ran the race in a “tabi”.

A tabi (足袋) is a “toed” fabric shoe/sock that has been worn in Japan (and parts of Asia) for thousands of years. Most commonly, tabis are made of cotton.

In 1912 shoes were still not very popular in Japan. Most of the populace worked barefoot, wore straw sandals, or wore tabis made of cloth.

Shizo was one of the first people to run a marathon in Japan in a cotton tabi and quickly discovered they fell apart after the grueling beating they took in 42 km of running.

He worked with a tabi store owner near his school to improve the design and many attempts later, he had a tabi that lasted the entirety of the race. Alas, this would prove no good in Stockholm, where unlike Japan, the roads he ran on were cobbled.

His tabi were torn to shreds. Overheated and exhausted, he was helped by a local family who gave him juice, buns, and a place to rest. Ashamed, he quietly returned to Japan without notifying race officials.

Although Shizo did not win the Olympics, he is considered the father of Japanese marathon running and his experiments with the tabi led to the success of many Japanese runners in later years and helped jumpstart Japan’s sports shoe industry.

A brief history of the tabi

The history of the tabi is complicated, but most people seem to agree that it started life is a simple piece of leather called a “tanpi” (単皮) wrapped around the foot. It is unclear at what point this simple piece of leather developed a split for the big toe, but it is believed the split toe allowed soldiers to control their movements precisely and was advantageous in battle.

Leather tabis trundled along till 1657, when the Great fire of Meireki burned 60-70% of Tokyo to the ground. After the fire, people started buying leather for its fire protection properties, leading to a shortage of leather in a country that had closed its borders to the world. Manufacturers switched to making tabis from cotton and other fabrics. And here is where the shoe started turning into a sock.

The next time you see someone dressed in traditional Japanese attire, pay attention to their footwear. Chances are they are wearing a white cotton tabi and walking on traditional Japanese slippers.

The cotton tabi too trundled along for another 250 years without major changes. It took a father refusing to send his son to trade school to change the history of the tabi.

The jika-tabi

In 1907, in a small town in Fukuoka, Shojiro Ishibashi was forced to take over his family's tabi business. Young Shojiro, though disappointed with his father’s decision, was full of ideas.

He quickly set about applying modern management principles to his business: scrapping order-made tabis in favor of standard sizes, turning unpaid apprentices into paid employees, introducing machines, and more. His goal was to standardize the production of high quality goods through mechanization and he succeeded by a mile. Soon, his company won hearts for making cheap tabis that were of high quality.

Not one to rest on his laurels, Shojiro set out to experiment with a material he saw a future in - rubber. His company developed a new kind of tabi made of thick cotton and a rubber sole. They called this a jika-tabi (地下足袋) which loosely translates to “tabis that touch the ground”. This married their expertise in fabric tabis and their experiments with a material that was relatively new to Japan. And turned the sock turned back into a shoe.

Shojiro’s idea was grounded in the economics and realities of the time. Commoners and farmers wore straw sandals that cost 5 sen (100 sen to 1 yen) and lasted a day. The average daily wage for a worker was 1 yen.

Shojiro’s jika-tabi cost 1.5 yen, but lasted six months and provided a far better experience. 18 yen per year vs. 3 yen per year for a better product was an easy choice. In just 12 months, Shojiro’s factory was pumping out 10,000 pairs daily.

Soon they branched out into shoes and other rubber products that I won’t go into the history of.

During the initial stages of WW2, the Japanese Imperial Army issued jika-tabis for their troops as a cheaper and more familiar alternative to leather boots. Legend has it that Allied soldiers in the Pacific War were able to identify the retreat of Japanese troops and movement of scouts just by looking at the distinctive marks left by their tabis.

Tabi in modern Japan

Today, tabis are still commonly used in Japan and continue to evolve. Pretty much every construction worker wears a specialized tabi, instead of shoes. This is because the tabis provide a great level of control and grip when walking in construction sites. Another advantage is that workers are able to wash the tabis with water at the end of the day and let them dry overnight, instead of wallowing in the sweat produced from working all day. Makes sense when you consider Japanese summers routinely go to 35°C (95 F) with 90% humidity.

Tabis have also been popularized in fashion by designers like Martin Margiela’s designs that the internet tells me has a cult-following.

The tabi has also inspired many varieties of running shoes. The famous Vibram five-toed shoes for example, used the tabi as a starting point. Many runners believe running in tabis allows better stability, comfort, and flexibility.

All this is well and interesting but what happened to Shojiro, you ask?

He and his brother went on to found a company that the world knows by the name Bridgestone. Bridgestone is now the world’s largest tire maker and was named after Shojiro’s surname "Ishibashi" (literally “stone bridge”).