The World's First App Store

Editor’s Note: This article ends on a cliffhanger. The next part goes out in a week.

I will start with an honest admission. I didn’t set out to write about the world’s first app store. I set out to write about Brother printers.

But doing my research, I stumbled upon something amazing they built in the 80s – the world’s first app store. And between “Awesome printer” and “World’s first app store”, the choice was clear.

Setting the Scene

The year was 1986 and Japan was at the peak of its economic miracle. Japan's technology industry was booming and personal computers were catching on like wildfire.

I watch a lot of older Japanese dramas and I find it shocking how in every new season there is a newer, slimmer, more capable computer.

Of course hardware is useless without software. And software was just flying off the shelves.

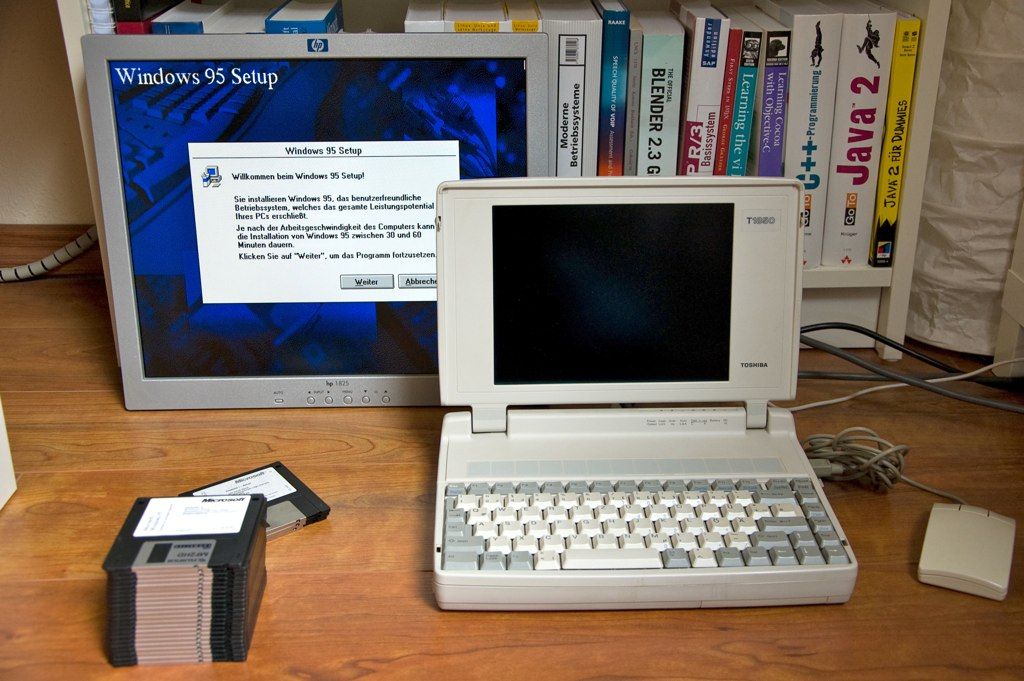

For our younger readers: In the medieval ages, software used to be sold in packages. In brick-and-mortar stores. You had to actually stand in line to buy software...

Software developers and game creators wrote their software, tested the hell out of it, and took their software to another company.

This other company copied the software on thousands of floppy disks or CDs, put them in cartons, and then shipped the cartons of software to shops across the country.

Had a bug in your software? Tough luck. Need to release an update? Lol, no.

Japan’s software market was so hot that retailers could not keep up with the demand. For highly anticipated games, shelves ran empty as soon as they were stocked. Getting new stock took time, leaving the creators, retailers, and customers, all sad.

Brother Industries

Enter Yuichi Yasutomo.

Yuichi worked at Brother Industries.

Brother was founded in 1934 and had its first success manufacturing sewing machines. Over the next few decades they built up a culture of tackling problems in domains they had no experience with, and the technical expertise to back it up. By the 1980s, they had their hands in everything from sewing machines, to typewriters, to washing machines, to CNC equipment.

It was in such an organization that the world’s first app store was born.

Three things came together for the world’s first app store to show up: technical prowess, changes to the law, and a booming market.

The Videotex

In 1985, Brother worked with the state monopoly telecom company, Nippon Telegraph and Telephone (NTT), to build a “videotex” network, a precursor to the internet (Wiki for the interested).

Brother's engineers contributed significantly in building compression algorithms to make downloads faster on this system. While videotex as a technology fizzled out, it left Brother's engineers with serious technical chops in data transmission.

The NTT Law

In 1985, the NTT Law was passed, privatizing all telecommunications. What used to be a state monopoly was now open to everyone. Anybody with the capital and skills could start their own phone, fax, or pager company.

A booming demand for software, the technical skills Brother had amassed, and the NTT Law – all this set the canvas that Yuichi’s team painted on.

Rethinking Software Distribution

Yuichi’s central insight was that people only cared about the contents of the floppy disk, not the disk itself.

If they could invent a machine that could sell the contents of the floppy disk and wrote that to an empty floppy disk, that would turn the world on its head – software need not be packaged, boxed, or trucked to a store.

Exploring different designs, the team landed on the idea for a “software vending machine” that would leapfrog all these pesky packaging problems.

They named it “Soft Vendor Takeru” (yeah, that sounds wrong in English but I must hurry to clarify that in Japanese long words are shortened to half. “Software” becomes “soft”, “hardware” becomes “hard”).

These vending machines were like no other vending machine people had seen. They had a screen, a floppy disk dispenser, a connection to Brother’s servers over the phone line, and a printer.

Here is how it worked:

- Put in money and buy an empty floppy disk

- Insert the disk into the vending machine

- Used the screen to choose the software you wanted

- Pay for the software

- Takeru downloaded the software from its server and wrote it to the floppy

- ???

- Go home with software!

If the software came with a manual (as it often did those days), the inbuilt printer would print that out for you.

It may sound clunky now, but in 1986 it was such a revolutionary invention that it quickly became an attraction. Forget empty shelves, you could simply download games that were out of stock!

1986 commercial for Takeru

Democratizing Software

This way of selling software had far-reaching consequences in the market.

Yes, it eased the problems of the creators, retailers, and customers, but importantly, it democratized software. For the first time, indie game developers who could never afford to package their games, could sell their creations.

They simply gave Brother a copy of their game and named the price they wanted. Brother took 30% of each sale and passed 70% back to the developer. Sound familiar?

Ahead of its time

Takeru was not just revolutionary, it was also way ahead of its time.

There were technical limitations that kept it from becoming a runaway success that could have changed the world. These problems would be solved eventually, but not quickly enough for Takeru.

“They asked me to turn Takeru into a 10bn yen business.

But the entire gaming industry was only worth 20 billion yen at that point...”

Yuichi Yasutomo, the father of Takeru Source: Twitter

Takeru's fundamental limitation was the telephone lines it relied on to download software.

Telephone lines only supported speeds of about 1.2 kilobytes per second. While games were much smaller then, each game still took up to 20 minutes to download.

This was 20 minutes where the user had to wait around doing nothing. This was also 20 minutes where nobody else could use the machine.

Brother did their best to work around this transmission speed problem.

They started caching copies of popular titles on the Takeru’s hard disk so they didn’t have to download it repeatedly. They built multiple generations of hardware, each better than the one before, and installed over 300 of these devices across the country.

They also realized stores were closed at night but telephone lines were not. They started sending software to the devices at night so users could quickly buy popular titles the next morning.

All of this helped Takeru slowly and steadily inch towards profitability. But in 1997, the service was shuttered after 11 years, despite finally turning a profit.

The (Half a) Billion Dollar Pivot

Yuichi says, “The company asked me to build Takeru into a 10 billion yen (~100m USD) business. The whole gaming industry was only worth 20 billion yen at that point. So unless we captured a 50% share, this was an impossible task. I turned my attention elsewhere.”.

While that does sound like a disappointing end to the world’s first app store, the thing Yuichi turned his attention to next, did become a massive hit.

The goldmine Yuichi stumbled upon made Brother the country’s #1 in a market worth half a billion dollars.

What market you ask? This one :)